Common nutrition and health issues in Eastern Europe

- ediensofficial

- 27 жовт.

- Читати 54 хв

Roman Rukavchuk, Liudmyla Kozlovska, Tayisiya Simochko, Nadiya Boyko

Eastern European (EE) traditional foods (TF): an introduction

The countries of the Eastern Europe Region (EER), including Belarus, Russia, North

Caucasus Region, Tatarstan, Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, have common

nutrition and health issues shaped by the long “common living” history under the Soviet

Union umbrella and unique shaped by their national way of developments.

To clarify which aspects mainly influence human healthdeconomic, cultural,

othersdthe most important factor is to discover an appropriate, standardized, and timely

commonly accepted methodology or way for detection and proving the evidence for a

strong connection, interaction, and correlation, in our case, between nutrition and

health. In other words, an accurate and realistic conclusion could be made based only

on clearly defined and exact statistical facts about the most commonly consumed foods,

data about their nutritional value, and the interrelationship with the health condition of

the population relevant to the consumption and nutrition indices.

The category of “often eaten food” is usually and typically represented by tradition-

ally (routinely) consumed national foods. These traditional (ethnical) dishes’ are mainly

dependent on a variety of a country’s unique factors that result in the formation of

so-called “national food perception” (D’Antuono and Bignami, 2012). Numerous papers

recently provide detailed descriptions of traditional foods (TFs). The various terms

proposed use different approaches. Some were mainly concluded after surveys made

by consumers and thus were oriented on their feelings and the behavioral acceptance

Nutritional and Health Aspects of Food in Eastern Europe

ISBN 978-0-12-811734-7, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-811734-7.00008-6

© 2022 Elsevier Inc.

All rights reserved. 187

of country- or national-specific foods categories. Others were based on points of histor-

ical developments of nutrition or diet traditions as a most crucial issue. Some novel ways

have been recently applied to find a more comprehensive definition of “ethnic food”

products through a synergistic combination of all the complex facets and sides of this

quite complicated subject (D’Antuono, 2013).

Finally, the simple definition of TF could be summarized as a nation’s commonly

accepted and culture uniqueness as represented by dishes and drinks, the recipes of which

have historical roots and were documented before the Second World War. The results of

a cross-cultural study devoted to all the trends in the developments of traditional foods

and all the factors influenced by modern technology, innovations, and challenges

affecting local food products have been well reported (Guerrero et al., 2009).

Thus, the cornerstones for TF are: (1) place, territory; (2) individual operation, cul-

ture, (3) perception of acceptance, (4) recognition; (5) transmission between generations

for at least for 25 years (understanding of “traditional” related to food as proposed by EC),

but only a few definitions are relevant to “nutrition.” EuroFIR has proposed a coherent

term for TF, which is very useful in the context of health influence issues as it includes

calculating the most important information about all food ingredients, their combination

and composition, and also processing and preservation methods (Dilis et al., 2013; Costa

et al., 2010; Slimani et al., 2007).

The list of exclusive descriptions of TF does not provide enough data to prove the

strong connection between food consumed and health conditions. To find a really strong

connection between often eaten preferential ethnic foods (products) and the health con-

dition of a population more investigations are needed. The required data should include

at least information about the biological active compounds of TFs, their varieties, local

differences in their content, microbial starters, and also information about typical pollut-

ants or xenobiotics, if any.

The first attempt to estimate the real direct influence of BSAC traditional foods and

their ingredients on human health was made by testing the content of different biolog-

ically active compounds in different traditional products of plant origin prioritized within

BaSeFood projects. These TFs belonged to six categories: (1) cereal or cereal-based foods;

(2) vegetables or vegetable-based foods; (3) fruit or fruit-based foods; (4) oilseeds or

oilseed products; (5) herbs, spices, and aromatic plants; and (6) low or nonalcoholic fer-

mented foods and beverages of plant origin. The obtained results of this multisectoral and

multidisciplinary research will be shortly concluded further, but clearly, such analytical

data collected for six BSAC countries are very valuable in making conclusions about

the possible health impacts. We also should note that EER during the last few years

have been subject to dramatic changes in their political and economic life. Thus in order

to understand the nutritionehealth connection axes we need overview first the speci-

ficity of the TFs of the nine above-mentioned countries and their behaviors or dietary

preferences, including the major characteristics of their cuisine. At the same time,

188 Nutritional and Health Aspects of Food in Eastern Europe

attention should be paid to the general changes in the mortality rates of the population of

the targeted EER countries.

An understanding of the main common background of the population’s food prefer-

ences and choices of these nine EER countries requires taking into account their histor-

ical context. The similarities of their natural “Slavic” or Soviet roots of post-USSR

countries during their common Soviet period has affected tremendously the formation

and development of nutritional behavior of this region’s people. Recognition of each

nation’ ethnic food priorities and their dramatic mixture in that time created a list of

so-called “Soviet national dishes,” which were mainly consumed on daily bases and

formed and maintained the health conditions of the population of all 15 Soviet Union

republics, including the countries and territories examined here.

From a Wikipedia source (Wikipedia contributors, 2020a), it is seen that the Soviet

Union foods list actually contains a mixture of different nationalities’ dishes and to esti-

mate the influence of eating behavior on population health before 1991 for all the Baltic

countries, Ukraine, and Belorussia (the Soviet Union recognized these countries as inde-

pendent on August 24, September 6, and December 25, 1991, respectively) this specific

“diet” and food preferences must be noted.

The food choices of the population of Russia, North Caucasus, and Tatarstan as well

as the rest of the reviewed countries are also related to their political and geographical

specificities. Three territories of Russia, Artsakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia, claimed

independence but are recognized by only a handful of entities. Abkhazia and South Osse-

tia are recognized by the global community as part of Georgia, and Artsakh as part of

Azerbaijan. Geographically, the North Caucasus region is known as the Ciscaucasus,

whereas the South Caucasus region is commonly known as the Transcaucasus. These

all feature different landscape characteristics. The Ciscaucasus contains most of the

Greater Caucasus mountain range. It consists of Southern Russia, mainly the North

Caucasian Federal Districts’s autonomous republics, and the northernmost parts of

Georgia and Azerbaijan. The Ciscaucasus lies between the Black Sea to its west, the

Caspian Sea to its east, and borders the Southern Federal District to its north. The two

Federal Districts are collectively referred to as “Southern Russia” (Wikipedia contributors,

2020c), and they have all experienced different traditional ethnic dishes and therefore,

nutritional and health issues.

Nevertheless, that data for Belorussia and Russia related to nutrition and health

statistics have not changed dramatically since independence, as the other factors (social,

economics) affect the mortality and levels of diseases to a much greater degree. It had

been shown that before the collapse of the Soviet Union, Belarus, Lithuania, and Russia

were quite comparable in terms of their socioeconomic development. Despite some dif-

ferences detected in the overall mortality levels, the three former Soviet republics were

also very close to each other in terms of mortality trends and age-specific mortality pat-

terns. After 1991, these three countries experienced substantial political and social

Common nutrition and health issues in Eastern Europe 189

transformations and many challenges associated with the transition from a socialist to a

market economy system. These sudden changes brought about numerous problems

also for other post-Soviet Union republics, such as rapid growth in unemployment, fall-

ing standards of living, and growing social and income inequalities. These factors contrib-

uted to the significant deterioration of the health situation in all the countries reviewed,

but the size and nature of the mortality crisis were different and country-specific. The

marked similarities in socioeconomic and mortality trends in the countries up to 1991

turned in contrast with their notable divergence during the subsequent years. The nature

and success of market reforms seem to be the most plausible explanation for these differ-

ences. Russia, Lithuania, and Ukraine have chosen more radical forms of economic and

political transformations, which have led to massive privatization campaigns. The reforms

were more sustainable and systematic in Lithuania compared to the other countries. By

contrast, Belarus has chosen a gradual and slow transition path and recent mortality trends

in Belarus correspondingly are contrasted with those observed in Lithuania, Ukraine, and

Russia. Including a cause-of-death, the analysis sheds more light on the plausible deter-

minants of the variations in mortality levels between the countries mentioned here and

the other EER countries (Grigoriev et al., 2010).

The interrelationship and strong correlation between nutrition and health conditions

can be proved by applying two different principal approaches.

The first is rather “cultural” and “behavioral” backgrounded methodologies and tools

which are simply oriented in the description of characteristics of the main ethnic foods

consumed by different nations and in parallel with reports available for their populations’

diseases and mortality rates registered by the FAO and other relevant authorities. Another

way and in our opinion much accurate, and is based on strong analytical examination of

traditional food nutrient value data, main food ingredients, the presence of beneficial bio-

logical active compounds (BACs), and all the detected compositional elements from one

side, and causal relationships with mortality and diet-relevant disease rates from the otherside.

One of the region’s most typical food- and nutrition-relevant diseases is obesity.

Overweight and obesity are defined as abnormal or excessive fat accumulation that pre-

sents a risk to health. A crude population measure of obesity is the body mass index

(BMI), a person’s weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of his or her height (in me-

ters). A person with a BMI of 30 or more is generally considered obese. A person with a

BMI equal to or more than 25 is considered overweight. Overweight and obesity are

major risk factors for a number of chronic diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular

diseases, and cancer.

To begin with, in the first approach, comparable and not analytic estimation and

description of the declared connection between these two groups of parameters (cuisines

in terms of “nutrition” and “rate diseases” level provided below for all of the selected in

countries). The population of Belarus in recent years has not changed significantly

(Fig. 9.1). The women/men ratio has also not changed recently and varied between 1 to

1.15 in 2019. As for urban and rural populations, there has been a tendency for the rural

population to decrease since 2019, and now it is about 21.6% of the population.

Concerning the morbidity of diseases of the digestive system among the adult popu-

lation of the Republic of Belarus for 2007e16, both general and primary morbidity are

observed in Minsk and the Gomel region. The most favorable situation is observed in the

Vitebsk and Mogilev regions. As for 2018, the highest mortality is in the Minsk region,

and the lowest in the Mogilev region. The downward trend in morbidity is characteristic

not only of the country but also for most regions (Mantivoda and Sineleva, 2019).

The main cause of mortality from 2012 to 2018 in Belarus was diseases of the circu-

latory system, while the lowest mortality was observed for diseases of the respiratory

system (Fig. 9.2) (Medvedeva, 2019).

The data for 2016 and 2017 demonstrate the differences related to food consumption

diseases measured for all the regions in Belarus introduced below (see Table 9.1).

In Belarus, 60%e65% of cases of type II diabetes occur in women (Public Health in

the Republic of Belarus, 2017). To connect these health issue data with Belarusian

cuisine one might note that “Belorussian” TF continued to maintain the closeness to

the cuisines of surrounding Slavic peoples, including Russians, Ukrainians, and Poles.

Also, these ethnic products are affected also by the influence of the cuisines of its

non-Slavic neighbors, such as the Lithuanians and Latvians. It is creating difficulties for

“distinguished” Belorussian dishes and such dishes are becoming less and less common in

the daily diet. First, the health and nutrition issues are correlated with the traditional use

of various types of “black flour”doatmeal, rye, barley, buckwheat and pea. The frequent

mixing of these various types and usage of rye flour for bread are also very typical in

Belarus.

Second, the predominant use of oatmeal and the ignorance of yeast has led to Belaru-

sian cuisine not actually recognizing either pancakes or pies is also one of its healthy habits

(Pokhlebkin, 2004).

The health issue or health influence of consumed foods is in the majority cases mainly

defined not by the components or ingredients themselves, but rather by the method of

cooking or food preparation techniques, traditional procedures, and preservation.

For example, Belarusian “pancakes” are completely different from Russian and

Ukrainian ones, since they are made from oat flour directly from raspda solution of flour

with waterdwhich spontaneously sours.

Several epidemiological studies have shown that the intake of whole-grain products is

associated with a reduced risk of type II diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, metabolic syn-

drome, and coronary heart disease, as well as cardiovascular mortality (Giacco et al., 2010;

Maki et al., 2010; Katcher et al., 2008). Empirical evidence shows that the consumption

of whole-wheat meals, like whole-grain bread, compared to white bread, even for 3 or

4 weeks, reduces total serum cholesterol level (Giacco et al., 2010), low-density lipids

(LDL) cholesterol, nonhigh-density lipids (non-HDL) cholesterol, triglyceride (Maki

et al., 2010), body fat, and abdominal obesity (Katcher et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2003).

This might be because of the high fiber content in this kind of bread. Furthermore, it

improved the bioavailability of vitamins and minerals, such as varieties of vitamin B,

calcium, and magnesium (Melanson et al., 2006).

Thus, it has greater diet quality and is attributed to a lower risk of cardiovascular dis-

ease (CVD). These facts make such products prepared without “yeast fermentation” a

relevant subject for health promotion.

This is important since self-fermented sourdough bread has been considered a healthy

food since ancient times. It is made using a sourdough starter composed of natural yeast

and lactobacilli (beneficial bacteria). Left to rise for 7e8 h and then baked, the bread con-

tains all the nutrients present in whole grains and, in particular, those in wheat germ. The

bread’s numerous beneficial effects are for the most part linked to two of its peculiar

characteristics: the sourdough starter and wheat germ (Capurso and Capurso, 2020).

This self-souring processing is commonly used in Belarus. Even when Belorussians

started using wheat flour at the time of the common Soviet Union history, they still

did not making it “yeast” fermented, instead applying soda as a baking powder.

The other products often consumed in Belorussia, Ukraine, and Russia as post-Soviet

countries are not differ significantly, so these cannot be calculated as factors in altered

population health.

Either typical vegetable-based dishes or pork or lamb meat are mainly used for cook-

ing homemade sausages, with similar procedures and preservation methods in all three

countries.

Even the differences detected in the consumption in Belorussia with a preference for

goose meat over chickens, which dominate in Ukrainian and Russian kitchens, could not

be reported or accepted as a crucial reason for any detected differences in food-relevant

health issues of the people from these countries.

The only significant effect on health can be recognized with food processing methods

or a large number of fermented foods that are consumed (Melini et al., 2019) and the

specific fermentation method.

Long-term and complex processing, which was used for grain or bran in folk cuisine

(including souring, malting, fermentation), caused such biochemical processes in these

simple products that greatly complicated their composition.

Thus, the main thing in traditional national Belarusian dishes in addition to special

combinations of flours for baked products that also differ from other countries is the pro-

cessing of ordinary and single products, which are subjected to complex, long, and often

combined cold and heat treatments that lead to a positive influence on human health.

Concerning the number of consumed products in Belarus there are illustrated in

Fig. 9.3 statistics for the changing ratios of consumed products from 2005 until 2019.

The increased amounts of meat, and fruits and berries, and decreased eating of bread and

bakery products with no changes for fish and only very slight reductions in milk and veg-

etables may be the reason for the relevant changes in the ratio of diet-dependent diseases.

Consumption of potatoes and meat per capita for Belarus (Table 9.2) (National

Statistical Portal, n.d.) was traditionallydas expecteddthe highest in the Commonwealth

of Independent States (CIS), when milk consumption was slightly lower than in

Kazakhstan, and egg consumption slightly lower than in Ukraine.

The general population of Estonia from 2000 to 2014 decreased, while from 2014 to

2020 it increased (Fig. 9.4). The women/men ratio increased from 1.13 in 2000 to 1.15

in 2020. Most of the population in Estonia is aged from 25 to 70 years.

Despite Estonia’s course to meet the global target for less low birth weight, there are

no sufficient data to assess Estonia’s progress for under-5 overweight, stunting, wasting,

and exclusive breastfeeding for infants. Estonia’s 2015 low birth weight prevalence of

4.3% has remained constant since 2000. Estonia’s adult population faces a malnutrition

issue: 25.6% of women of reproductive age have anemia, and 7.7% of adult men have

diabetes, compared to 6.5% of women. Meanwhile, 21.8% of women and 20.3% of

men are obese.

The mortality rate for the Estonian population and relevant statistics can be found in

Deaths (n.d.), where it is stated that at least half of deaths are caused by diseases of the

circulatory system that gradually increase with age and there is evidence of a clear

connection between nutrition and health (Fig. 9.5).

Coming to the issue of the Estonian cuisine, the most interesting feature is probably

the strange, untypical or almost indispensable combination of cooking components: milk

with peas and fish, potatoes as a component of a confectionery, making its unique uses

and technology of such unusual combinations that are unforgettable and extremely tasty

and healthy. There are no significant differences in the most typical food raw materials for

Estonian cuisine, and the vast majority of the foods are boiled rather than fried. Of course,

some Estonian dishes are fried, but they are not part of the national TF and are rarely

used, especially in comparison with the other EER countries, including Ukraine,

Belorussia, and Russia.

Another national characteristic of Estonian traditional foods’ processing is the very

small and specifically applied seasoning, such as onions, dill, marjoram, caraway, and

very rare parsley and celery.

The overwhelming majority of dishes are prepared completely without spices and

seasonings.

The strongly prescribed seasoning combination (dill in herring, marjoram in blood

sausages, cumin in cottage cheese, and parsley and celery in meat soups), with boiling

is accomplished with two traditional cooking approaches: (1) to use for boiling various

liquids in addition to water, for example kvass, milk, dairy-flour, dairy-sour cream,

and milkeegg mixture, and (2) not using any oil or butter for fried dishes (again only

milky-sour cream or a milky-flour concoction) have resulted in very healthy trends

and nutrition behavior.

This does not mean that Estonian cuisines are not tasty, since the variety of technol-

ogies used for boiled, semiboiled, semifried, and always semicooked with cream and sour

cream in its pure form, also the so-called “castmed”dmilk and milk-sour cream gravies

following the unusual and interesting combinations of products (fish with lard, apples

with bovine blood, peas with milk) allow for tremendous tasty and at the same time

healthy and unique TFs.

Estonian cooking traditions and the main ingredients potentially connected to con-

sumer health are relevant for the following national specificities, namely: (1) technologies

of using natural preservatives free from impurities, natural taste of food raw materials;

(2) huge variety of milk-containing dishes such as milk-dough, milk-cereals, milk-

vegetable, milk-fish, milk-mushroom, milk-egg, milk-beer, and even milk-milk soups,

prepared from unleavened milk contrast greatly with lactic acid soups of Central Asian

and Transcaucasian cuisines; (3) no seasoning, no fat, not fried, various unusual combi-

nations of boiling/mixing raw materials; (4) separate/single meat preparations and

consumption of meat mainly as a second dish; (5) mixed cereals, vegetable cereals, and

vegetable porridges, similar to Latvian putram, but somewhat different both in compo-

sition and in the absence of a fermentation process and in the strict constancy of their

combinations; (6) eating vegetables in pure form but not as separate dishes and obligatory

flavored with lard, butter, sour cream, and milk, as well as milk gravy but not with onion

Common nutrition and health issues in Eastern Europe 199

or dill; (7) potato retains pride of place as in Belorussia and Ukraine, but then cabbage and

peas are second, followed by carrots; (8) finally, among all the Baltic cuisines, and of

course the other EER countries described here, except probably Russia, Estonian

consumes the most fish. These specificities and ethnic food characteristics could be spec-

ulatively translated into their potential health effects: the first is relevant to lower con-

sumption of salty and fried products and different/specific methodologies of

preservation, namely no chemicals/antibiotic-based preservation that can negatively

affect human health; the second is connected to the consumption of milk-based dishes

which are dominant in the Estonian kitchen and which mainly replace the meat/

vegetable-based dishes which simplifies the digestion process, as is also true for points

(3) and (4) above; and the fifth specificity is difficult to interpret as “healthy” habits as

mixed components and no fermentation process is rather less beneficial compared to

eating fermented products, while the sixth point is in line with the principles of the

now widely known keto-diet that, in addition with point (8) proves the good influence

on the health of Estonian population, when the seventh point is rather neutral but only in

the case that the food basket has big variety.

The nutritional habits are connected not only to alimentary tract disease, as defined by

low safety and quality of consumed foods and drinks but also to the different so-called

metabolic diseases: from atherosclerosis via obesity and diabetes type II to cardiovascular

diseases.

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) contribute greatly to inequalities in health in Europe.

The CVD death rate in Ukraine is the highest in Europe and is sevenfold higher than in

France (which has the lowest). There is also a striking difference in CVD mortality

between European Union (EU) members before the enlargement in 2004 and Central

and Eastern European (CEE) countries that joined the EU in 2004 and non-EU coun-

tries. The difference in CVD mortality between West and East Europe grew during the

1970 and 1980s when rates declined in the West and either remained the same or rose in

the CEE countries. Political reforms at the beginning of the 1990s, which were followed

by great socioeconomic changes, coincided with further diversification in CVD mortality

in CEE countries. Diverse trends in CVD mortality were followed by larger gaps in life

expectancy between West and East Europe and within the CEE. Rapid development of

high-technology treatment procedures, which followed the economic recovery of the

CEE countries, would have only limited influence on the overall control of CVD. Expo-

sure to classic risk factors might largely explain the longitudinal trend in falling CVD

mortality in some countries, but it is unlikely that it could explain rapid changes in the

others. Still, large potential to control the disease lies in developing effective preventive

policies with targets to lower exposure to the classic CVD risk factors. The recent history

of CVD in CEE countries makes the “alcohol hypothesis” less convincing as an expla-

nation for CVD mortality trends and differences between East and West Europe. The

hypothesis that dynamic changes in CVD mortality in CEE countries are triggered

200 Nutritional and Health Aspects of Food in Eastern Europe

and explained largely by psychosocial factors is attractive. However, there is not enough

evidence for the last hypothesis (Pająk and Kozela, 2011). Similar research has been

conducted recently, and the tendencies of CVD developments/trends are reported.

Using the latest available data, CVD causes more than four million deaths each year

across Europe, accounting for 45% of all deaths. CHD and cerebrovascular disease were

the most common causes of CVD deaths, accounting for 1.8 million and 1.0 million

deaths, respectively. The number of deaths from CVD is higher in women (2.2 million)

than men (1.8 million), with CVD accounting for 49% of all deaths in women and 40%

of all deaths in men. With similar numbers of men and women dying from CHD, these

sex differences arise from a greater number of women dying from cerebrovascular disease

and “other cardiovascular diseases” (Fig. 9.6).

Poor-quality diets are high in refined grains and added sugars, salt, unhealthy fats, and

animal-source foods; and low in whole grains, fruits, vegetables, legumes, fish, and nuts.

They are often high in processed food productsdtypically packaged and often ready to

consumedand light on whole foods and freshly prepared dishes. These unhealthy diets

are facilitated by modern food environments, a problem that is likely to become more

widespread as food environments in low/medium-income countries shift to resemble

those of high-income countries (Anand et al., 2015).

According to recent studies (Stefler et al., 2020), nine food groups were identified

which were regularly consumed by rural communities in the 1950s/early 1960s in several

Eastern European countries. These were: (1) bread and grain products, (2) potatoes, (3)

legumes, (4) storable vegetables, (5) preserved fruits and vegetables, (6) dairy products and

egg, (7) poultry, (8) processed meat products, and (9) lard for cooking. Analyses of these

data illustrate that individuals who adhered closely to the traditional Eastern European

dietary pattern had higher risk of deaths from all-causes and from CVD compared to

those who did not follow such a diet. Therefore, traditional food should be studied

more and the overall dietary pattern should be considered.

The total population of Latvia (both males and females) is decreasing from 1990s. The

urban population is much larger than the rural one (Fig. 9.7), and the women/men ratio

increased from 2000 to 2012 and decreased from 2012 to 2019 (Central Statistical

Bureau, 2019).

In 2017, 42.7% of the Latvian population aged 16 and over had suffered from a long-

standing (lasting for more than 6 months) illness or health problem.

In 2016, the male obesity prevalence for Latvia was 21.6%. This parameter in Latvia

increased from 14% in 1997 to 21.6% in 2016, growing at an average annual rate of

2.31%. In 2016, the female obesity prevalence for Latvia was 25.1%. Between 1997 and

2016, the female obesity prevalence of Latvia grew substantially from 22.3% to 25.1%,

rising at an increasing annual rate that reached a maximum of 0.88% in 2003 and then

decreased to 0.80% in 2016. Once considered a problem only in high-income countries,

overweight and obesity are now dramatically on the rise in low- and middle-income

countries, particularly in urban settings (Latvia Male Obesity, 2020).

Although the life expectancy of the Latvian population has increased significantly

since 2000, it remains the lowest in the EU (Fig. 9.8), and major disparities persist by

gender and socioeconomic status.

The life expectancy for Latvia in 2020 was 75.32 years, a 0.18% increase from 2019.

Poor health outcomes are largely a product of the prevalence of unhealthy behaviors that

are very similar to Ukraine, as well as low levels of health spending.

The health system is underfunded and, despite recent progress, remains excessively

hospital-centric. The health status of the population could be improved by reducing

out-of-pocket payments and shifting the focus to prevention, primary care, home

care, and community-based services (OECD, 2017). Lifestyle-related risk factors account

for half of all deaths in Latvia. In 2014, one in four adults smoked dailyddown from one

in three in 2000, but still well above the EU average. The total figure masks a large

gender difference, with 37% of men reporting smoking daily in 2014. In the same

year, one in five Latvians reported engaging in heavy alcohol consumption regularlyda

proportion close to the EU average. The obesity rate was the second highest in the EU in

2017, with more than one in five Latvians being obese (Tisenkopfs et al., 2015). General

statistics of the healthcare system and dynamics of diseases in Latvia could be found at

Data Catalog (Health, 2020).

A very interesting report by The Diversity of Effects of EU Membership on Agricul-

ture in the New Member States claims that similarly to the majority of European coun-

tries, many countries lost some of their agricultural areas after EU accession. Latvia and

Lithuania, however, increased their utilized agricultural area (UAA) between 2003 and

2007. Agricultural employment in new member states (NMS) continued to fall after

EU accession also. For example, agricultural employment in Bulgaria and Lithuania

decreased by close to 40%. The decrease was more than 20% in Latvia. Capital as another

factor of production is usually measured in agriculture by the stock of assets per hectare of

agricultural land. There are huge differences among countries regarding asset endow-

ment. Countries with high agricultural production capacities (except Poland) lag behind

in asset endowment. In 2004, Slovenia had the greatest amount of asset endowment (total

assets/UAA), while the lowest was in Latvia (Slovenia had 16 times higher asset endow-

ment than Latvia in 2004) (Csaki and Jambor, 2009).

There is a very typical and very healthy tradition of Latvian people to eat a lot of salted

and pickled herring and smoked fish (eel, herring), as well as onions or scallions in their

natural form or included separately in a cuisine that is very similar to that of the Ukrai-

nians and Russians. Baltic herring contains omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin D, and has a

beneficial impact on cardiovascular diseases, mortality, and the risk of depression (Tuo-

misto et al., 2020). Onions are rich in flavonoids and the alk(en)yl cysteine sulfoxides

which have benefits for human health, such as anticarcinogenic, antiplatelet, antithrom-

bic, and other properties (Griffiths et al., 2002).

In Eastern Latvia, caraway seeds are added to dairy dishes, following the example of

Lithuanian cuisine, which has antioxidant potential and overall quality of protein bread

(Sayed Ahmad et al., 2018). Lard, smoked meat and cold cuts are often used with

mustard. To sum up the taste range of Latvian cuisine, it can be considered as moderately

204 Nutritional and Health Aspects of Food in Eastern Europe

sour/salty (Pokhlebkin, 2004; Wikipedia contributors, 2020d). Grains are also widely

used, from porridges to baking patties. The most popular bread in Latvia is made from

rye. Potato is “the second bread” for Latvians and also for Ukrainians, thus it is often

used in main courses, soups, and even salads. All these indicates that the traditional

Latvian diet and dishes are healthy. The national survey data demonstrate an increase

in the consumption of fruit and milk, while there has been a drop in potato and fish con-

sumption by Latvians. From 2016, compared with previous years, changes may be

observed in the consumption of certain food products and this probably explains some

of the positive tendencies observed in health condition of Latvians since these dates. Still,

it is very difficult to be sure of a connection between the nutrition and health condition

issues based only on these registered changes. This interrelationship is rather controver-

sial, since consumption of some food products is reducing, which is partly because house-

holds choose to eat outside home or have changed their eating habits/diet. Consumption

of potatoes, sugar, fish, cabbage, butter, margarine, and vegetable fat have dropped, while

consumption of milk, pork, poultry, fruit, local garden fruit, and drupes have increased.

The decline in consumption of sugar and potatoes may be influenced by the increase

in consumer prices (11.8% and 10.0%, respectively), but also probably an increased

understanding of the nutritional impact on human health. Survey results show that in

2016 one household member on average consumed 47 L of milk, 14 kg of cheese and

curd, 31 kg of bread, 207 eggs, 19 kg of fresh pork, 12 kg of fresh poultry, 21 kg of

sausage products and smoked meat, 62 kg of potatoes, and 5 kg of fresh fish. In respect

to fruit, the greatest numbers per household member annually were recorded in

consumption of local garden fruit and drupes (21 kg), tropical fruit and berries (11 kg),

and citrus fruit (10 kg) (Central Statistical Bureau, 2018). This gives an overall image

of Latvian dietary habits, which are rather healthy, especially in regard to the consump-

tion of local fruits and drupes. These are sources of biologically active components, which

have a positive impact on health (Sanlier et al., 2019).

The total population of Lithuania decreased from 3 502 000 in 2000 to 2 760 000 in

2019 (Fig. 9.9). The urban population increased (to 67.68% of the population in 2018).

Lithuania is on course to meet the global target for low birth weight, but is off course

in meeting the targets for anemia in women of reproductive age, male diabetes, female

diabetes, male obesity, and female obesity. Lithuania has no prevalence data available for

under-5 overweight, stunting, or wasting. There are also insufficient data on exclusive

breastfeeding among infants. Lithuania’s 2015 low birth weight prevalence of 4.5% has

decreased slightly from 4.8% in 2000.

Lithuania’s adult population faces a malnutrition burden, and also 25.5% of women of

reproductive age have anemia, and 8.9% of adult men have diabetes, compared to 7.1% of

women. Meanwhile, 27.8% of women and 24.2% of men are obese (Lithuania Nutrition

Profile, n.d.). Lifestyle-related risk factors account for more than half of all deaths in

Lithuania. Alcohol consumption is higher than in the majority of EU countries. In

2014, one in five adults reported smoking on a daily basis, with a rate of over one in

three among men. Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death, accounting

for nearly two in five deaths. More than half of people aged 65þ reported having

one or more chronic diseases. One-third of all deaths in 2017 were related to dietary

risks (including low fruit and vegetable intake, and high sugar and salt consumption),

which is nearly twice the EU average (32% Lithuania, 18% EU). Recently, people

with diabetes type II (T2DM) had an excess mortality risk, which was higher in women

than men (Linkeviciute-Ulinskiene et al., 2020). One of the possible and obvious

reasons for such a situation is the budget of the health system, which is smaller than

in other EU countries (OECD, 2019).

A 2013 survey on the dietary habits of Lithuanians showed that they tend to have an

unhealthy diet: not consuming enough fresh fruits and vegetables and an average intake

of fish that is lower than the recommended amount. Only 21.3% of the adult population

admits to taking dietary decisions according to health criteria. Price is the determining

factor that affects the choice of food (Commission of the European Union, 2015). Other

studies also showed that school-aged children have low intakes of fruits and vegetables,

which leads to high rates of CVD and cancer risks. Therefore, increases in the consump-

tion of fruits and vegetables should be promoted, along with a reduction in the intake of

less healthy choices, such as soft drinks and high-fat, high-sugar snack foods, by reducing

social inequalities in food consumption (Zaborskis et al., 2012).

The total population in Russia has not changed dramatically since 2000 and the

female/male ratio is also quite stabile (Fig. 9.10). The urban population increased from

73.2% to 74.6%.

The mortality rate in Russia significantly decreased recently (from 16.0 in 2000e05

to 12.7 in 2015e20 per 1000 population), especially for children under 5 (from 19.3 in

2000 to 5.8 in 2019, deaths per 1000 live births) (Country Profile, 2020).

However, the number of people who have some kind of disease increased every year

and in 2019 in total almost 3,476,000 people were ill, in contrast to 2,381,000 in 2000

(Federal State Statistic, n.d.). The largest number of diseases per year is diseases character-

ized by high blood pressure. Its frequency increased more than threefold compared to

2000 (Table 9.3).

According to recent research, the consumption of milk and dairy products (28.9%

lower than norm) vegetables, and cucurbits (23.6% lower than the norm) and fruits

(41% lower than the norm) is lower than the dietary intake levels, while consumption

of bread products is much more than the norm (117 kg at a norm of 96 kg), potatoes

(96 kg at a norm of 90 kg), and sugar (39 kg at a norm of 24 kg) (Kulikov and Minakov,

2019).

Russia’s food environment falls short in offering healthy choices at affordable prices.

The availability of vegetables and fruits is lowest in Russia compared to other countries in

the WHO European Region. Most Russians face nutritional problems linked to

unhealthy diets like other post-Soviet Union countries. Almost 60% of Russia’s adult

population is overweight, and more than one in four (26.5%) is obese. The prevalence of

overweight and obesity in Russia has been increasing over the past 3 decades. In adults, it

is higher among women, whereas in childhood, rates are higher among boys. Compared

to their Central and Eastern European counterparts, Russians have the highest mean en-

ergy intake, with total fat as the main source, mostly provided by monounsaturated fat.

Unhealthy diets create risk factors for various cardiovascular diseases, cancers, chronic dis-

eases such as diabetes and osteoporosis, and many more. Attributable to the Russian diet

that has remained high in unsaturated fat and salt, and low in fruit and vegetables, partic-

ularly outside harvest season, disorders of the circulatory system increased by 18%, endo-

crine disorders by 18%, and neoplasms by 16%. Overweight and unhealthy nutrition are

underlying risk factors for cardiovascular diseases and cancers, which together with in-

juries account for 78% of deaths in Russia (Lunze et al., 2015).

The North Caucasus region, as part of Russia, especially Chechnya, Ingushetia, and

North Ossetia, is in the grip of an ongoing humanitarian crisis marked by conflict and

poverty. The health system is unable to sufficiently meet the demands of the 1.5 million

people affected by the crisis, 50,000 of whom are internally displaced, 27,000 living in

temporary accommodation centers in Chechnya, and about 47,000 people are living

in temporary settlements in Ingushetia. The main health priorities in the North Caucasus

are maternal and child health, communicable and vaccine-preventable disease control,

tuberculosis control, sexually transmissible infections and HIV/AIDS control, rehabilita-

tion of health structures, mental health and psychosocial rehabilitation, and antipersonnel

mine victim supportd this strategy was reported by the WHO (WHO, 2006).

Nevertheless, Caucasian people are the longest living population in Russia and across

the entire world.

The Caucasus region is known for having many people who live to be 100 years and

more. One of the most well-known among this group was Magomed Labazanov, a resi-

dent of Dagestan, who died in 2012 at the age of 122.

While the average life expectancy of ethnic Russians is about 72 years, the Caucasian

republics (Ingushetia, Dagestan, Kabardino-Balkaria, etc.) have a much higher figure.

People in Ingushetia, for example, often live up to 80 years, according to official statistics

(2017). That is why it is worth learning their secrets on how to stay active and cheerful as

long as possible.

Included in the list of scientifically and practically proved dishes connected to such

longevity are a variety of fermented milk products specific to these regions (ayran, mat-

zoni, narine) accomplished with local honey, and cheesedsalted suluguni and adygei

cheese which are very often mixed with adjika, and leaves of mint and coriander. These

types of cheese are unique as starters and also as they contain only 20%e30% fat. The

main everyday dish is thick porridgedmamalygadwhich is prepared from corn flour

and is as common as bread. Oil or sour milk cheese can also be added to mamalyga.

Corn can be a dessert for adults and children, and churek is another dish made from

210 Nutritional and Health Aspects of Food in Eastern Europe

it, which is sweetened with honey or stuffed with cheese and walnuts. Corn has low

levels of the amino acid tryptophan. People in the Caucasus region enjoy mutton,

lamb, and beef, and khinkali is one of the festive dishes. This is a broth with lamb and

flatbread made from dough. Other traditional dishes include fried chicken and chicken

cooked on a spit, boiled chicken with adjika, and stew of fowl in nut sauce with herbs.

Caucasians eat a lot of vegetables, and prepare dishes from beans, kohlrabi leaves, beetroot

tops, and cabbage. Salads are often seasoned with adjika, walnuts, and greens (coriander,

dill, and parsley). Spicy food helps to normalize blood pressure, as well as improve the

blood circulation. Walnuts are also used frequently, and contain seven times more calo-

ries than beef and have proteins, fatty oils, carbohydrates, and amino acids that are neces-

sary for health. Many tourists take churchhela home from the Caucasus. This delicious

dessert is made from nuts, flour, and grape or pomegranate juice. Caucasians also eat hon-

ey, baklava (pastry of phyllo dough and nuts), halva, and sweet fruit more often than

processed desserts. Red wine is made by many Caucasian families, and some joke that

three glasses of red wine is an essential part of your daily diet for a longer life (taken

from “Russia beyond,” written by Maria Bunina; Bunina, 2020).

Coming back to published recently statistical data about overweight people depen-

dent on the geographical location, place of living, gender, age, etc. in different regions

of Russia, including North Ossetia (Alania) Republic (North Caucasus), and the situation

is similar in this region to St. Petersburg and not comparable with other regions of Russia

(Figs. 9.11 and 9.12) (Kontsevaya et al., 2019).

In Tatarstan, since 2010, when the latest All-Russian Population Census of the

population was performed, the number of centenarians has more than doubled.

At the beginning of 2019, 371 residents over 100 years old lived in the Republic of

Tatarstan: 83 men and 288 women. Moreover, in 2010, there were only 156 such elderly

residents in the region.

In addition, there has been a decrease in the gender disparity among long-living

Tatarstan residents, although it remains in accordance with general demographic patterns.

“If, according to the results of the 2010 census, men aged 100 years and older were

almost seven times less than the number of women in this category, then at the beginning

of 2019 this difference decreased markedlydup to 3.5 times” (TatarstanSTAT).

The new All-Russian Population Census was due to be held from 1 to 31 October,

2020, using digital technologies, however it was delayed to 2021. All collected data

were to be accumulated in the Big Data format, as previously reported by the IA

“Tatar-inform”. More details are available at: https://www.tatar-inform.ru/news/society/

01-12-2019/v-tatarstane-rastet-chislo-dolgozhiteley-preodolevshih-vekovoy-rubezh-569

7270.

From other (scientific) research-oriented data it was reported that the connection

between FTO gene polymorphism with carbohydrate metabolism disorders and the

risk of developing DM2 in the Republic of Tatarstan has been proved. The positive

correlation of the FTO gene A allele with early carbohydrate metabolism disorders was

revealed, which allows groups with increased risk for dysfunctions of carbohydrate meta-

bolism to be identified. Apparently, the A/T polymorphism of the FTO gene is mostly

associated with the secretory function of pancreatic beta cells (Valeeva et al., 2018).

In this and other reports/papers the situation in relation to type II diabetes and obesity

in Tatarstan has been investigated, as shown in Fig. 9.13 the type II diabetes/obesity

distribution in 75 regions of Russia is good evidence for the lowest incidences registered

for Tatarstan and North Caucasus.

This fact is clear evidence of different culture and food differences influencing human

health conditions (Dedov et al., 2017).

The food of modern Tatars, keeping the main traditions of Tatar cuisine, has under-

gone significant changes. In connection with the forced resettlement of the Tatars and

the associated loss of national culinary traditions, vegetables and fruit began to occupy

a more significant place, and the range of fish dishes expanded, with mushrooms,

tomatoes, and salt entering everyday life. Fruit and vegetables that were previously

considered exotic and made available through international trade have become more

common (Pokhlebkin, 2004; Tatar National Dishes, n.d.).

The total population of Ukraine has decreased since 2000 and is decreasing every year

(Fig. 9.14). The female/male ratio increased from 2000 to 2010 and then decreased to 1:

1.15. The population aged 10e24 has decreased, while those aged 55e59 has increased

(World Population Prospects, n.d.).

An interesting study was performed in Ukraine in 2000. At that time, 39% of men and

49% of women were overweight. Predictably, it was found that the risk of being over-

weight increased dramatically with age: about 47% of men and 60% of women were

overweight in the 40þ age groups. Among young men (under 40), those consuming

more fruit (OR 1⁄4 0.31) and more physically active (OR 1⁄4 0.43) were less likely to be

overweight. In women over 60, those overweight were more physically active

(OR 1⁄4 2.32). In men over 40 and women below 40, the prevalence of overweight

was lower in smokers than nonsmokers. Eating potatoes, meat, and milk was associated

with increased BMI in some groups. No consistent associations were found for the con-

sumption of fish, butter, oil, sugar, and vegetables, or for education.

Thus, the authors made an interesting conclusion about the connection between spe-

cific traditional food consumption and obesity trends. They stated that being overweight

was more likely related to increased use of traditional foods like dairy products, meat, and

potatoes. Still, in the 2000s, the Ukrainian population did not bear patterns of obesity

epidemics found in the West, since no associations with either socioeconomic status or

foods usually associated with overweight were found. Smoking was related to lower

BMI in populations with a high prevalence of smoking (Chagarna and Andreeva, 2014).

The number of newly registered cases of diseases has a decreasing tendency

(Table 9.4), and the most common were the respiratory diseases. However, mortality

is relatively high, in 2018 more than 587,000 people died and the main cause of death

was CVD, killing more than 234,000 in 2018. Ischemic heart disease was the top cause

of death in 2017 (State Statistics Service of Ukraine, 2019). Dietary risks are also very

high. According to recent studies, food consumption in Ukraine should be changed

by increasing the consumption of meat and meat products, fish and fish products, fruits,

berries, and grapes (Batyr, 2019; Babych and Kovalenko, 2018).

Ukrainian cuisine is widely known among Slavic cuisines. It has long spread far beyond

the borders of Ukraine, and some Ukrainian dishes, such as borscht, varenyky, and

dumplings, have entered the menus of international cuisines and are generally healthy

TFs.

The favorite and most consumed product is lard, both as an independent dish, mainly

fried, in the form of so-called crackling, and in the form of a variety of spices and fatty

bases of a wide variety of dishes. Eating high-fat dishes in general is recognized as a

risk factor initiating CVDs, but there are some clinical trials demonstrating that frying

with lard is preferential as it has been proved to be safe (Talbot, 2011).

An abundance of flour products is very characteristic of Ukrainian cuisine. The

national dishes are products made from simple yeast-free dough: dumplings, grechaniki,

varenyky, cakes, and newer confectionery products, such as verguns and stavbits. The

wheat flour is almost exclusively used for these cookies. Vegetables are mainly used as

side dishes for fatty meat foods or served as independent dishes with bacon. Ukrainian

cuisine is also characterized by the use of different varieties of legumes and especially

beansdthis is one of the healthier habits. Preferred vegetable and plant crops include

beets, carrots, cabbage, pumpkin, corn, potatoes, and onions. Corn, like beans, is

more often used as an additive.

Of the spices and seasonings, the most popular are onions, garlic, dill, cumin, anise,

mint, lovage, angelica, savory, and red pepper, and imported spices include bay leaf, black

pepper, and cinnamon (for sweet dishes). Of the fruits and berries loved in Ukraine,

soaked, fresh, dried, and smoked-dried, cherries, plums, pears, currants, watermelons,

apples, and raspberries can be considered as national favorites. Along with fruits, modern

Ukrainian cuisine uses abundant quantities of sugar and molasses, both in pure form and

in the form of components of uzvar, preserves, and especially jam and confectionery,

what can be rather unhealthy.

All these facts give us indications that traditional food in Ukraine is not very healthy,

and that often it has more fat then needed. Studies have also shown that there are special

aspects of eating behavior that permit assessment of children’s health state as early alimen-

tary disease, manifested in excessive body mass, a deficiency of essential vitamins, min-

erals, and food fibers, and functional disorders of digestion (Podrigalo et al., 2017).

Correspondingly, general nutrition value before 1990/1992 was calculated based on

so-called nutritional tables. Western researchers have paid considerable attention to the

economic and political issues associated with the imbalances between the supply of

and demand for livestock products and other quality foods in the Soviet Union. Over

the last 2 decades, growth of discriminatory income and the maintenance of low and

increasingly subsidized retail prices along with greater awareness of the wider availability

of a variety of foods in the West and in some Eastern European countries have increased

Soviet consumers demands for high-quality food. Also, the composition of the food sup-

ply has changed somewhat to reflect consumer preferences in the Soviet Union which

has not solved the economic problem of providing a food supply that matches consumer

preferences (Lane et al., 1987).

There is an interesting report based on a comparable study of the nutrient content of

the Soviet food supply in comparison with the US food supply that for the years from

1965 till 1981 included changes in per capita levels of calories and nutrients which is

no longer confidential and fully publicly available as a CIA report (CIA, 1999).

Another issue is that data provided was not always accurate for a number of different

reasons, some of which are listed below. “The problem with this is that sources who are

trying to do the same (USDA and FAO) get different results. FAO’s series looks like

USDA unadjusted series. But FAO’s series also look like Allen’s, and Allen’s are supposed

to take losses into account. So someone is making a mistake somewhere. We could

perhaps believe the official Soviet data rather than FAO’s. But according to FAO, the

GOSKOMSTAT surveys have two problems: one is that it oversamples lower income

households and that the coefficients used to convert food kg into calories are

15%e20% lower than FAO’s. They conclude that “with such large differences, it is

Common nutrition and health issues in Eastern Europe 217

difficult to say much about the level of caloric consumption with any confidence”. And

even if we took the official consumption data that supposedly would be accounting for

losses it is still far from the similar figure for US intake from USDA, so differences in

methodology must be present. Thus the conclusion is then that, based on the data above,

Soviet caloric intake was high enough to say Soviet citizens were reasonably well fed, in

terms of calories” (Ricon, 2016). There are large differences in various sources, for example,

in numbers provided by FAO data about Soviet Union food nutrition and those provided

by Soviet statistics. Correspondingly, it is very difficult to come to a common conclusion

about the eating preferences of those in the Soviet Union people, since this subject is very

complicated.

The first food composition tables were published at the end of the 19th century

(Colombani, 2011). Nowadays these are very complex instruments that include not

only tables stored in databases, but also many different additional IT instruments for oper-

ating such data and carrying out complex analysis. Some instruments, such as Foo-

dExplorer by EuroFIR, include many food composition databases (FCDB) and make

it easy to operate with all the data simultaneously.

Many new tools and improvements in food composition databases have been devel-

oped, such as LanguaL, which helps with a standardized description of food. LanguaL is

widely used in almost all food composition databases and is a de facto standard (Finglas

et al., 2014).

The nutritional and elemental composition of traditional Belarusian dishes is insuffi-

ciently studied. Based on FAO and EuroFIR data, no publicly available FCDBs have

been created for this country (Giertlova, 2018). There are isolated initiatives to create

appropriate tables for products, and in 2018 the number of registered products was

146. For traditional dishes, known “collection of technological maps of Belarusian

dishes” it regulates only the composition at the level of products for tables and features

of their preparation. For more detailed study of such conditions, commonly used direc-

tories (Kurgan and Gaiduk, 2017) are often used.

Estonia has developed a national FCDB, which has more than 3620 of the most com-

mon foods in its territory. The first version was created in the early 1990s, and since 2009,

due to active cooperation with EuroFIR, its structure has been improved. Currently, the

database contains data from 267 sources and is constantly updated. The last update took

place in June 2020. The database has a graphical interface and is available at: https://tka.

nutridata.ee/. The database contains data not only on energy values, but also on the full

composition of products, with a maximum of 60 nutrients.

A common database on the composition of Latvian food products has been devel-

oped, which includes more than 600 products, data on which are obtained from various

sources, including from producers. The database also contains a method of preparation of

the product and a list of raw materials that are especially useful for people with various

218 Nutritional and Health Aspects of Food in Eastern Europe

food intolerances or allergies. The generally accepted LanguaL approach is used to

describe the products in the database. Unfortunately, there is no available web interface

for the database, but such access is possible through third-party tools, such as

FoodExplorer from EuroFIR.

According to the literature data, a composite food database is available for Lithuania,

but it is not available online and the year of its creation is mentioned as 2002. It is stated

that it is available through FoodExplorer from EuroFIR, but there is no detailed infor-

mation about it.

A food composition database in Russia doesn’t exist according to the FAO and there

are only food composition tables, which were last updated in 1985. However, there is an

online resource, http://web.ion.ru/food/FD_tree_grid.aspx, where you can find infor-

mation about the chemical composition of common foods. There is no detailed informa-

tion about this database or when it was created and which data were used to create it.

Analytical and other data collected by national compilers for all the countries in

which food composition data available can be found at the FAO official website

(INFOODS, n.d.).

Despite the Eastern European region TFs being well investigated and known in general

(Food and Agriculture, 2007; Trichopoulou, 1992), and there being numerous data on

recipes and related historicalecultural descriptions (Trichopoulou and Lagiou, 1998; Naska

et al., 2006), nutrition and health claims of the chosen EE foods and drinks remain incom-

pletely studied and therefore they are the subjects of great interest.

Current (actual) data on Ukrainian and Russian TFs were partially characterized and

defined within the BaSeFood project based only on prioritized dishes belonged to six

different groups: cereals, vegetable, fruit- and oil-based TFs, herbs and spices, and finally

fermented products and low or nonalcoholic content beveragesdall of them plant-

originated foods or drinks and all of them being selected and prioritized additionally as

products with the “highest potential health claims value” (Naska et al., 2000; Prieto-

Ramos et al., 1996). This could be an excellent example of how the documentation

on traditional food and their health claims, and also composition data, should be prepared

and analyzed.

According to this, the documentation of the traditional character, in addition to the

EuroFIR definition (Serra-Majem et al., 1993), is a prerequisite for the food (TF) being

integrated into the national documented file within the BaSeFood project. The national

files are excel files containing information on the origination of the traditional foods, its

traditionality, consumption of the food or its wider food group, availability of composi-

tion data, and references supporting all the collated information.

Based on these and some additional informationdprovided below criteria, of course,

not all of the EE cuisines may be reported as cuisines with “healthy” properties. For such

statements many careful studies are needed.

Common nutrition and health issues in Eastern Europe 219

Evaluation criteria considered for the finalization of the list of valuable selected

ethnical foods with potential national nutrition value in the EER should be based on:

(1) health claims and nutrient profiling; (2) food biodiversity and food composition;

(3) target bioactive components with putative health effects; (4) technological/cooking

safety criteria; and (5) good marketing potential.

To identify the nutrition profile and beneficial health input on humans of all the

promising EER0 foods, at least the different biological active substances and fiber, vita-

mins, minerals, etc. need to be included.

Such examinations had been analytically performed and the national documentation

file includes TF foods of plant origin belonging to the above-mentioned TF categories

within BaSeFood: (1) cereal or cereal-based foods; (2) vegetable or vegetable-based

foods; (3) fruit or fruit-based foods; (4) oilseeds or oilseed products; (5) herbs, spices,

and aromatic plants; and (6) low or nonalcoholic fermented foods and beverages.

By default all the foods included in the files contain bioactive substances (Naska et al.,

2008).

The nutritional composition (water, ash, total protein, total fat, individual fatty acids,

total sugars, starch, and total dietary fiber) of traditional foods from Ukraine and Russia

in this project has been determined using a common approach with standardized and

harmonized procedures (Costa et al., 2013; Albuquerque et al., 2013).

From the five analyzed foods of the Russian Federation, four are mainly constituted by

water and one is only constituted by fat since it is oil. The buckwheat porridge crumby also

has a significant amount of carbohydrates and about 5% of total dietary fiber because it is

prepared from buckwheat. Regarding minerals, buckwheat porridge crumby was the food

with the highest mineral content from the analyzed foods for the Russian Federation. K

was also found in vegetable okroshka and watermelon juice. The only mineral quantified

in kvass southern was Na and none of the analyzed minerals were found in mustard oil.

From the traditional foods selected for the Russian Federation, mustard oil was the only

one with vitamin E (1.1 mg/100 g of edible portion) and watermelon juice with vitamin

C (2.26 mg/100 g of edible portion). Vitamin B2 was found in small amounts in three

Russian Federation foods (buckwheat porridge crumby, vegetable okroshka, and water-

melon juice) ranging from 0.03 to 0.08 mg/100 g of the edible portion.

Regarding Russian Federation traditional foods, total folate was only found in buck-

wheat porridge crumby, lycopene in watermelon juice, and a-carotene in vegetable

okroshka. However, b-carotene was found in vegetable okroshka (181 mg/100 g edible

portion) and watermelon juice (48.7 mg/100 g edible portion).

As for Ukraine, of the seven foods selected, one is mostly composed of fat, another is

primarily composed of carbohydrates, and the others are mostly composed of water.

Besides a high fat content, roasted sunflower seeds have also a high protein content

(20%) and a considerable total dietary fiber content (about 11%). This total dietary fiber

content was similar to sour rye bread (about 9%). Regarding minerals, the selected foods

for Ukraine were those that presented the highest mineral content. The major minerals

220 Nutritional and Health Aspects of Food in Eastern Europe

found in these traditional foods were Na, K, Ca, Mg, and P. Roasted sunflower seeds

showed higher values for K, Ca, Mg, and P. As for vitamins and carotenoids, trans-

carpathian green borsch and cottage cheese with dill and garlic were not analyzed

as they were lyophilized. The other four analyzed Ukrainian foods all presented

with vitamin E, and vitamin C was only found in roasted sunflower seeds

(1.78 mg/100 g of edible portion). The highest vitamin E value was found for uzvar

(6 mg/100 g of edible portion), which was the only Ukrainian food without total

folate. On the other hand, in this group, roasted sunflower seeds had the highest total

folate content (113 mg/100 g of edible portion). Ukrainian borsch and sauerkraut pre-

sented lycopene, a-carotene, and b-carotene, although Ukrainian borsch had much

higher levels of these carotenoids. Roasted sunflower seeds presented only lycopene

(29.6 mg/100 g of edible portion) and uzvar only b-carotene (62 mg/100 g of edible

portion) (Costa et al., 2012).

Other papers recently published about BAC in different foods, about their direct

influence on human health, and their connection with the quality of food ingredients.

The use of cornelian cherry is associated with the popular perception of health-

promoting properties: disinfectant, antidiarrhea, antiinflammatory, and vessel-

protectant, especially against hemorrhoids (D’Antuono et al., 2014). Another study

investigated the effects of plant extracts on cellular markers of endothelial function

(eNOS activation and expression and ET-1 secretion). Treatment of human umbilical

vein endothelial cells with persimmon extract significantly increased Akt and eNOS

phosphorylation and nitric oxide metabolites and significantly decreased secretion of

ET-1 to the media after 24 h compared with a vehicle control. These results suggest

that persimmon fruit contains bioactives that can improve endothelial function via acti-

vation of eNOS and reduction in ET-1 secretion, but that dill, kale, Sideritis, and nettle

do not (Danesi et al., 2013). There are also results that illustrate that bioactive-rich

extracts of kale and pomegranate that are consumed as traditional plant foods of Black

Sea area countries were effective in modulating platelet function (Konic-Ristic et al.,

2013).

Despite the presence of large databases containing biologically active substances in

plants and foods in general, such as ePlantLibra and PhenolExplorer (Neveu et al.,

2010; Plumb et al., 2016), data on their contents are incomplete.

Another attempt had been made to summarize all the other evidence of food and

health interrelationships in the Encyclopedia of Food and Health (Caballero et al., 2015).

It has been recently shown that high intakes of fruit and vegetables are associated with

a decrease in cardiovascular diseases via endothelial protection. Thus the most important

fruit/vegetables and bioactive compounds to prevent endothelial diseases are berries,

apples, virgin olive oil, tomatoes, soybeans, and polyphenols, carotenoids, and unsatu-

rated fatty acids, respectively. The bioactive compounds from fruit and vegetables

Common nutrition and health issues in Eastern Europe 221

provide endothelial protection through the following mechanisms: improved eNOS/

NO bioavailability, attenuates oxidative stress, inhibited NF-kB pathway, and decreased

cell adhesion molecules expression (Monsalve et al., 2017).

The reliable and high-quality food composition data presented in this study are a key

tool for future food consumption surveys. Information on food description, sampling

plan, sample handling, component identification, method specification, and value and

quality assessment was collected for the prioritized traditional foods, enabling the provi-

sion of documentation to support the inclusion of new data in the available national

FCDBs.

The use of a common methodology for the study of traditional foods enables the

other EER countries to further investigate their traditional foods. Moreover, a knowl-

edge base of traditional foods from any country contributes to promoting local biodiver-

sity, rural development, and sustainable diets by maintaining healthy dietary patterns

within local cultures (Trichopoulou et al., 2002).

Nutrition and well-being of traditional food in targeted Eastern

European countries (EER)

The nutrition and food perceptions of the EER population are somewhat controversial

topics. As was demonstrated recently, food consumption priorities determined as results

of comprehensive international questionnaires have national and cultural specificities, but

nonetheless taste and price dominate perceptions of value, not the nutritional or health

impact.

Dietary data for nutrition monitoring and surveillance can be derived from three main

sources: food balance sheets (FBS), household budget surveys (HBS), and specifically

designed individual nutrition surveys (INS). The Food and Agriculture Organization-

assembled FBS provides information on food supply at the population level. Household

budget surveys are systematically conducted by National Statistical Offices in country

representative population samples and aim at collecting, among others, data on food

availability at the household level. Individual-based surveys, when participants’ intakes

are recorded as accurately as possible, provide the best evidence on food consumption.

Being expensive and labor intensive, however, representative individual-based surveys

are regularly undertaken in only a limited number of countries, usually those with robust

economies and years of experience in the field.

Documenting and monitoring dietary patterns are among the prime contributions of

food sciences in the development of nutritional epidemiology, the formulation of dietary

recommendations and the planning of national food, nutrition, and agricultural policies.

Diet represents an unusually complex set of exposures that are strongly intercorrelated.

Early efforts have been focused on identifying the specific nutrients that may be responsible for effects on people’s health. Current data, however, suggest that apparently

favorable effects cannot be exclusively attributed to specific components and in several

instances these components may act synergistically. International comparisons of dietary

exposures have primarily been based on food rather than nutrient intake. The food data

used for international comparisons are often derived from: (a) food balance sheets (FBS),

providing information on food supply at the population level; (b) household budget sur-

veys (HBS), collecting data on food availability in the household; and (c) specifically

designed individual nutrition surveys (INS), providing information on the food intake

of free-living individuals, over a specified time period.

The FBS had been completed nationally, on the basis of the annual food production,

imports and exports, changes in stocks, and agricultural and industrial uses within a coun-

try, as well as losses during storage and transportation. When these have been taken into

account, the remaining quantities represent the commodities that can be assumed to have

been used for human consumption in the country. The per-person supply of food

commodities is obtained by dividing the respective quantity by the population partaking

of it. International comparisons based on the time series FBS data, in conjunction with

information from other sources, can help to ascertain trends in the food supply of one

country in comparison to others.

The households data in national surveys data are required for the exact analytical esti-

mation or prognoses about food influences on human health.

In the context of the Sustainable exploitation of bioactive components from the Black Sea

Area traditional foods (BaSeFood) project (http://www.basefood-fp7.eu/), food supply

data from FBS and food availability data from HBS were retrieved for the six participating

countries, with Ukraine and Russian Federation among them, in order to describe

dietary patterns in the region. This dietary information is jointly described below with

mortality patterns, using data retrieved from the World Health Organization databases.

Household budget surveys provide information on foods and beverages available for

consumption to a nationally representative sample of households. The members of the

participating households are asked to record information on all foods and beverages avail-

able in the household during a reference period, including purchases, contributions from

own production, and food items offered to members as gifts. The survey is implemented

over a period of a year, with due attention to capturing seasonal variations in food intake.

Information on the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the household

members is also recorded, allowing analyses of the effect of socioeconomic determinants

on food choices.

Introduction to the food balance data of targeted EER

According to the WHO, almost 41 million people died of noncommunicable diseases in

2016, which is equivalent to almost 71% of all deaths (World Health Organization,

Common nutrition and health issues in Eastern Europe 223

2020). The major causes were: cardiovascular diseases (17.9 million deaths), cancer (9.0

million deaths), chronic respiratory diseases (3.8 million deaths), and diabetes (1.6 million

deaths). Cardiovascular disease and diabetes are related with lifestyle, particularly with

food intake patterns, with respect to the quantity and variety of foodstuffs.

The following countries were considered in this study: Tatarstan, North Caucasus,

Russian Federation, Ukraine, Belorussia, and also the Baltic countries.

Food balance sheets (FBS) from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United

Nations (FAO) were the primary source of information for the present comparison

(INFOODS, n.d.).

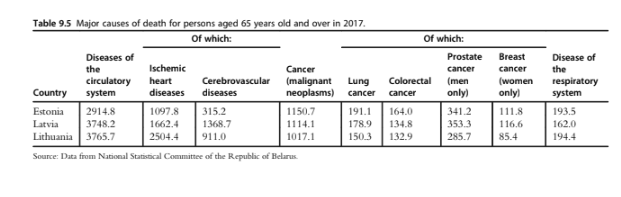

Generally, the results for 2017 indicate relatively high standardized death rates among